3 Reasons Why You Need To Lift With A

Full Range Of Motion

By David Kathmann, MS, RSCC,

CSCS, NSCA-CPT

Written on April 30, 2014

Exercises

preformed with a limited range of motion, whether intentional or not, are

fractions of a lift. Lifting with a

short range of motion does not get to be called a full lift. For example, a squat performed above parallel

(parallel being the crease of the hip just below the top of the knee) is not

considered a full squat; rather it is a fraction of the squat. Any lift that isn’t performed correctly and

with the proper range of motion is simply cutting yourself short. Put your ego

and previous knowledge aside, drop the weight, and start reaping three benefits

of lifting with a full range of motion.

- Get stronger

1.

Get

stronger – We all know “Half-Rep Harry” at the gym. This is the guy that

thinks he is impressing everyone with how much weight he is lifting, but only

moves those weights half way (or less!) through the proper range of motion.

Yes, it is true that you can lift more weight through a partial range of

motion, but it does not impress anyone. Check your ego at the door and start

moving those weights through a full range of motion. Moving weights through a

full range of motion engages more muscles and muscle fibers (1,3,4). This results in more testosterone and growth

hormone production to aid in muscles strength, growth, and a drop in body fat

(5). Performing exercises over a full range of motion requires more work; and

yes it is harder, but harder leads to stronger gains.

As you get stronger

with a full range of motion, you naturally will get stronger through the

partial ranges of motion too, but it doesn’t necessarily work the other way

around. Lifting with a partial range of motion only strengthens the muscles

through that specific range, leaving the rest of the range weak. Utilizing a

full range of motion strengthens the muscles utilized through their complete

range of motion. Lastly, as muscles get utilized over a full range of motion

and get stronger, the tendons must also get stronger leading to a decreased

chance of injury during sporting events.

As you get stronger

with a full range of motion, you naturally will get stronger through the

partial ranges of motion too, but it doesn’t necessarily work the other way

around. Lifting with a partial range of motion only strengthens the muscles

through that specific range, leaving the rest of the range weak. Utilizing a

full range of motion strengthens the muscles utilized through their complete

range of motion. Lastly, as muscles get utilized over a full range of motion

and get stronger, the tendons must also get stronger leading to a decreased

chance of injury during sporting events.

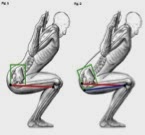

2. Better for the joints – Lifting with a partial

range of motion gives the lifter false confidence in the amount of weight his

body can truly handle and is most apparent when it comes to the joints (2). Heavy, unaccustomed weights load joints and

their associated ligaments and tendons heavier than they can handle. This

overload can cause damage to the joints, ligaments, and tendons. Lifts

performed with partial ranges of motion can lead to inflammation in joints,

tendonitis, and/or some other injury. However, exercises performed over a full

range of motion with proper form and with weights that can be safely handled

allow muscles and their tendons to take part in stabilizing and protecting the

joints, without improperly overloading the joint (4). Side note - Incorrectly performed exercises do not get to label a

correctly performed movement as “bad” or “dangerous”.

Hamstrings help keep the knee

neutral when squatting properly.

3. Gain flexibility – Moving weights

through a proper, full range of motion allow the muscles to stretch and

contract over a longer distance. As mentioned above, lifting weights through a

partial range of motion only strengthens (and moves) the muscle through that

specific range of motion. A common half-rep exercise is the bench press. Many

people like to bench press with the elbows only going to 90 degrees because

they feel it is “safer” on the shoulders and they can move heavier weights.

However, the muscles, especially the pectoralis major (“the pecs”), only move a

short distance and only get strengthened through that short range of motion.

This causes the pectoralis muscle to shorten and draw the shoulders forward

into a rounded position. Moving the weight through a full range of motion and

letting the pec muscles stretch, while getting stronger throughout a full range

of motion, can solve this shortening issue (as well as balancing out upper body

pushing movements with pulling movements). This same principle can be applied

to many other lifts and provide increased flexibility throughout the entire

body with minimal time spent with static stretching (6).

Put the ego aside, learn the proper

form for each lift (i.e. squat, deadlift, overhead press, pull up, and bench

press) and start moving through a full range of motion. Yes, the weights may be

significantly lighter, but consistent focus on lifting through a proper range

of motion will ultimately lead to bigger strength gains, happier joints, and

increased flexibility.

Disclaimer:

Photos in this article are not property of Pro Fit Strength and Conditioning

and are intended only for visual entertainment.

REFERENCES

1. Clark,

D.R.; Lambert, M.I.; and Hunter, A.M. Muscle Activation in the Loaded Free

Barbell Squat: A Brief Review. J Strength

Cond. Res. 26(4): 1169-1178, 2012.

2. Drinkwater,

E.J.; Moore, N.R.; and Bird, S.P. Effects of Changing From Full Range of Motion

to Partial Range of Motion on Squat Kinetics. J Strength Cond. Res. 26(4): 890-896, 2012.

3. Paoli,

A.; Marcolin, G.; and Petrone, N. Influence of Different Ranges of Motion on

Selective Recruitment of Shoulder Muscles in the Sitting Military Press: an

Electromyographic Study. J Strength Cond.

Res. 24(6): 1578-1583, 2010.

4. Pinto,

R.S.; Gomes, N.; Radaelli, R.; Botton, C.E.; Brown, L.E.; and Bottaro, M.

Effect of Range of Motion on Muscle Strength and Thickness. J Strength Cond. Res. 26(8): 2140-2145,

2012.

5. Shaner,

A.A.; Vingren, J.L.; Budnar Jr, R.G.; Duplanty, A.A.; and Hill, D.W. The Acute

Hormonal Response to Free Weight and Machine Weight Resistance Exercise. J Strength Cond. Res. 28(4): 1032-1040,

2014.

6. Simao,

R.; Adriana, L.; Salles, B.; Leite, T.; Oliveira, E.; Rhea, M.; and Reis, V.M.

The Influence of Strength, Flexibility, and Simultaneous Training on

Flexibility and Strength Gains. J

Strength Cond. Res. 25(5): 1333-1338, 2011.

2014 Pro Fit Strength and Conditioning www.pfstrength.com